- WHITEPAPER

Making the Business Case for Supplier Diversity

The combined business, ethical and reputational argument for supplier diversity is compelling

June 2023

Foreword

It should be obvious – our supplier base should reflect the diversity of our organisation and its stakeholders.

In reality, this is easier for some to achieve than others. Supplier diversity can be difficult to measure and even more difficult to build a compelling business case for – beyond a moral argument. However, that is the challenge many procurement managers now face – how to convince your numbers-focused CFO that resources should be put into supplier diversity over mandatory requirements such as Modern Slavery Act compliance or Payment Times Reporting Act compliance? Or for that matter, corporate policy, Indigenous procurement support, your Net Zero plan, social procurement efforts, the use of SME suppliers or buy local policies? Which is first?

This whitepaper, produced in partnership with ArcBlue, provides guidance on how to get the buy-in required to commit to taking action on supplier diversity. The array of ESG initiatives are not mutually exclusive and can often work in tandem to deliver on multiple goals as part of the one project. This whitepaper will give you the information you need to prioritise your initiatives and build a compelling business case for supplier diversity that speaks to the needs of your organisation and its stakeholders.

Jonathan Dutton FCIPS

Chief Executive, PASA

Executive Summary

This whitepaper encourages organisations to take an ambitious approach to supplier diversity to maximise meaningful change through inclusion, social impact and better business outcomes.

This whitepaper begins with an exploration of the increasing pressures on businesses to embrace supplier diversity. It then provides guidance for organisations to prepare an internal business case to get support from their senior leadership to implement supplier diversity. The whitepaper then concludes by identifying some of the key challenges organisations face when beginning their supplier diversity journey and provides tips for managing them.

Introduction

Sustainable Procurement

Organisations worldwide are increasingly seeking to better leverage their procurement to achieve greater secondary benefits beyond simply the goods and services being procured, this is often referred to as sustainable procurement.

Sustainable procurement seeks to ensure that all procurement activities are undertaken with consideration of economic, environmental and social impacts and ensuring meaningful and measurable secondary benefits are obtained.¹

Specifically, sustainable procurement aims to reduce negative impacts the procurement activity whilst maximising positive outcomes (e.g., supplier diversity, reducing carbon emissions and modern slavery risks from supply chains or increasing resource efficiency, supplier diversity or local economic resilience).

The term ‘sustainable procurement’ is used in this whitepaper, however, there are other terms that encapsulate some or all of these concepts too, including ‘corporate social responsibility’, ‘social procurement’, ‘ESG – environmental, social and governance’, ‘local or place-based procurement,’ ‘responsible supply chains,’ and ‘broader outcomes’.²

Sustainable procurement is a key mechanism to create supplier diversity within supply chains.

Supplier Diversity

Supplier diversity is “a practice that encourages diversity in the supply marketplace by encouraging the purchase of goods and services from businesses owned by, or that assist, underrepresented groups”.³

The underrepresented businesses will vary between communities and industries but can include businesses such as those owned by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, Māori and Pasifika peoples or women. It can also include social enterprises, small to medium enterprises and local or regional businesses.

Supplier diversity also seeks to influence business practices within supply chains by providing opportunities to suppliers that demonstrate inclusive employment or provide training and development opportunities to underrepresented people. This may include people with disabilities, immigrants, ex-offenders and young people that are not in employment, education or training.

Part 1: The key drivers behind supplier diversity

Supplier diversity’s potential social and economic impact is far-reaching, growing new businesses and employment for owners and workers from backgrounds that all too often have been excluded from such opportunities. Increased spending on diverse suppliers can generate life-changing access and possibilities for people within underrepresented groups.

There are increasing pressures on organisations to embrace supplier diversity and a key driver behind this is governments. Many governments are progressively seeking to leverage their significant procurement activity to advance their social and sustainable policy objectives, including diversity and inclusion. This is particularly relevant in the current environment where social and economic disadvantage has been exacerbated due to factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic, increased cost of living pressures and uncertain global events.

Government procurement represents between 13-20% of countries’ gross domestic product.⁴ As more government procurement seeks to achieve social and sustainable outcomes, this has a significant influence on the private sector and society, helping to further support sustainable outcomes.

In addition to government requirements, there are also growing expectations from shareholders, customers, and staff for organisations to be diverse and inclusive. This includes understanding and responding to intergenerational disadvantage and misconceptions, and unconscious and conscious bias. From a procurement perspective, there is also growing pressure to ensure supply chains more closely reflect their communities and provide opportunities for local people and businesses.

Part 2: Making the business case

According to the Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply, companies spend more than 70% of their revenue on procurement. This is a significant amount and puts procurement leaders in a unique position to reimagine the scope of procurement’s influence and respond to business and stakeholder needs by harnessing this spend to drive positive diversity outcomes.

Armed with a solid business case, procurement leaders are in a stronger position than ever to demonstrate the strategic value procurement teams can bring to their organisation and its stakeholders and communities.

However, if organisations are serious about creating meaningful impact through supplier diversity, they will need to make changes to the way they conduct their procurement and supply chain activities.

This will require support from senior leadership to champion supplier diversity and to make it a priority for the organisation. It will also require investment up front to establish the necessary foundations including, time, money, resourcing, education and capability development.

Convincing leadership of supplier diversity can be challenging, making it important to mobilise all available arguments to gain traction. An awareness of likely challenges at the very outset helps manage expectations and build a more effective framework while mapping realistic outcomes and impact.

So how do you prepare the business case?

At the heart of a strong business case is being able to persuasively articulate the ‘why’ and pre-empt the audience’s concerns. Organisations do not have finite resources and budget available, and they face many competing pressures, so the business case needs to be stronger than simply “supplier diversity is the right thing to do.” Here are some key considerations to consider when preparing a business case:

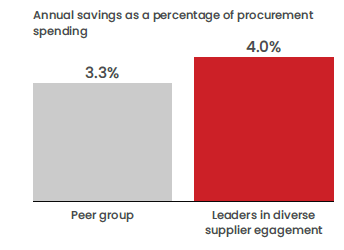

Increased savings

Data shows that expectations of paying a premium for supplier diversity is often misplaced. Organisations that spend the most on diverse suppliers save an additional 0.7% on their total procurement costs, according to figures gathered by Bain & Company and Coupa.⁵

Workforce attraction and retention

Engaging with a greater range of suppliers is increasingly essential to meet the expectations of staff and increase attractiveness to prospective hires, consumers, clients and investors on issues of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI). At a time of pervasive labour shortages in many markets, issues of sustainability and diversity have become a key differentiator to attract talent and retain staff. Multiple surveys in recent years have found that most respondents consider DEI and other corporate social responsibility programs non-negotiable. This is particularly the case among millennials and Gen-Zs.

Values that align with the organisation’s stakeholders’ own values are an increasingly influential factor in the decision making of consumers as well as workers. A study on behalf of Coca-Cola found shoppers who were aware of the brand’s supplier diversity program were 45% more likely to view it as valuing diversity, with just under half also saying they were more likely to buy Coca-Cola products.⁶

Winning business

As many multinationals and governments deepen their commitments to supply chain diversity, organisations that cannot demonstrate it are increasingly likely to lose business as a consequence. Implementing strong policies and commitments to supplier diversity can not only avoid lost business, but also open up new commercial opportunities particularly with government buyers who are more likely to have supplier diversity requirements.

Risk reduction

The mitigation of supply chain risk is particularly important during the current period of global pressures related to Covid-19 pandemic triggered disruption, disconnection and inflationary pressures that continue three years later. Supplier diversity can help to reduce some of the risks that may appear on organisations’ enterprise risk registers. For example, supplier diversity offers greater opportunities to localise supply chains and reduce reliance on a handful of larger providers. It also introduces greater competition and potential for cost reductions in the value chain.

In this context, greater diversity increasingly aligns with supply chain priorities by growing flexibility and resilience. After the onset of the pandemic in 2020, global manufacturing executives surveyed by Bain & Company and the Digital Supply Chain Institute in late 2020 cited these two characteristics as their key areas of focus. In pre-pandemic iterations, cost was the overwhelming priority.⁷

Compliance

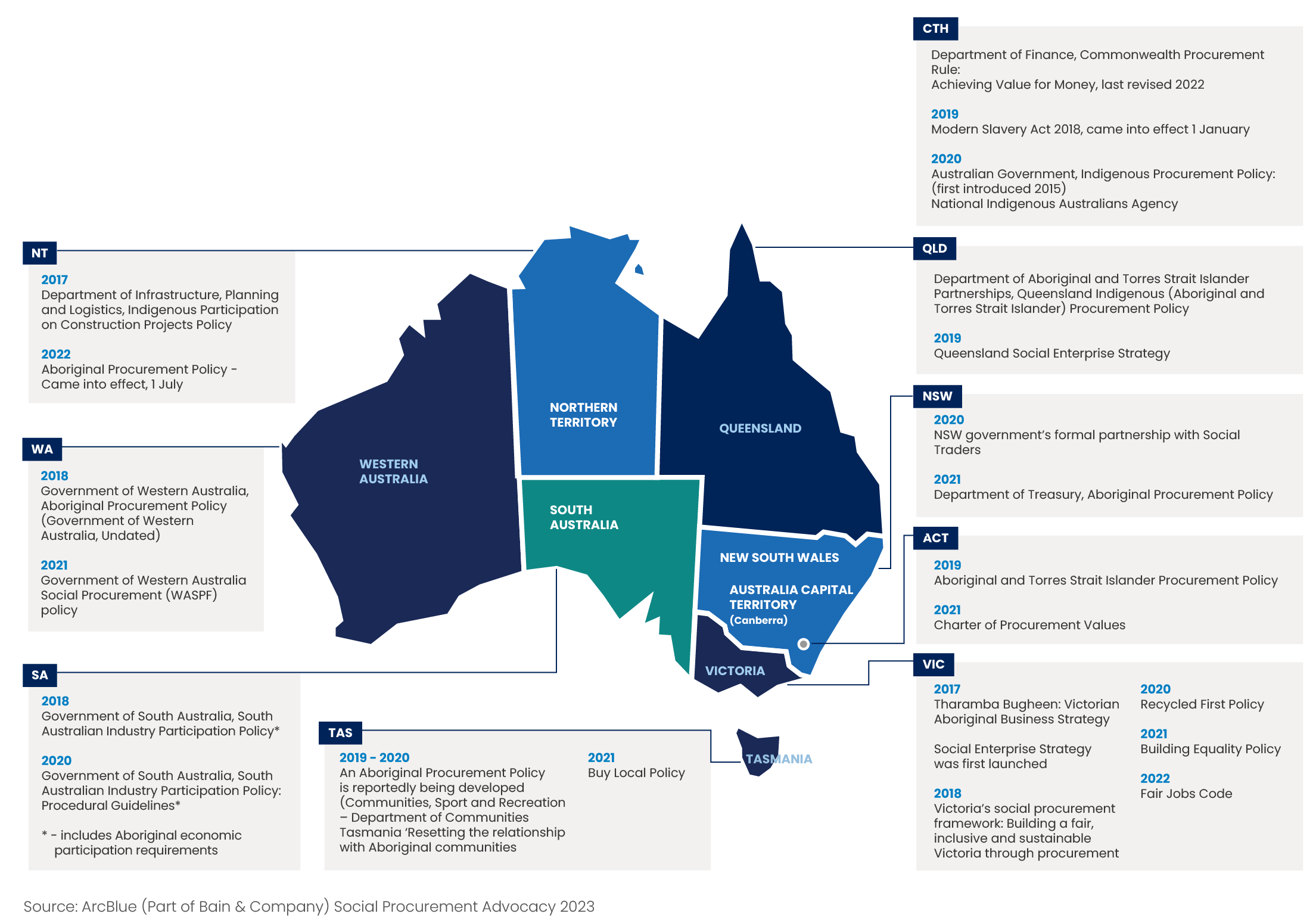

In Australia, in addition to Federal-level regulations, all eight State and Territory governments have at least some form of procurement framework or guidelines relating to sustainable procurement and supplier diversity.

This is similar in New Zealand with both central and local government having several policies requiring public procurement to achieve sustainable outcomes. Most of these include requirements on the inclusion of Indigenous, Māori and Pasfika owned businesses, SMEs and local and regional businesses and focus on driving local social and economic benefits within their communities.

Social licence to operate

Having a diverse supply chain can support an organisation’s ‘social licence to operate.’ Meaning that the community it operates in has confidence that the organisation will behave in a legitimate, accountable, transparent and socially and environmentally acceptable way that is not just compliance driven and is informed by a wide range of stakeholders.⁸ Having a strong social licence can help to lower business risks and provide greater operational certainty.

Innovation

By better reflecting the diversity in society, a broader supply base allows organisations to gain new perspectives across the spectrum of lived experiences. It also provides access to new insights and ideas that allow organisations to better understand and serve both existing and new markets. This helps organisations in two major ways. First, new mindsets and approaches help foster innovation, including helping to inform and identify new products and solutions as well as challenging and influencing markets. Second, engaging with suppliers from diverse communities can better enable organisations to reach into those communities to expand their customer base.

Greater collaboration

Many diverse suppliers are often more willing to listen and respond to customer needs, including working with their customers to co-design solutions and support market expansion. Since diverse suppliers are frequently smaller organisations, they also bring the added benefit of greater responsiveness and agility. As such, they can quickly adapt to new ways of working and may be more willing to adopt a bespoke approach that delivers targeted innovations. They also often place a heavy emphasis on client retention and long-term relationship building.

Supplier diversity helps organisations to gain better understanding of and build stronger relationships with their communities and better understand and address their needs.

Part 3: Challenges and taking the first step

Alongside the business case, organisations need to have a clear plan to successfully implement supplier diversity. To succeed will require organisations to have ambition to look beyond spend targets, an openness to change and an understanding of the potential pitfalls.⁹

ArcBlue has identified five interlinked barriers to success, and potential solutions to help organisations overcome them in building a diverse supplier base:

CREATE A JOINED UP APPROACH

ESTABLISH PRIORITIES AND DRIVE CULTURAL CHANGE

DEDICATE RESOURCES

SPEND ON ALL SUPPLIERS

DRIVE INCREMENTAL CHANGE

Conclusion

Supplier diversity initiatives can create powerful competitive advantages by improving the performance of procurement, as well as creating a variety of strategic benefits.

The possibilities and opportunities supplier diversity opens up to underrepresented groups in society may be harder to quantify. But armed with a comprehensive business case, procurement teams are best placed to present the collection of arguments in favour of supplier diversity to their organisation.

Procurement leaders are also guiding their businesses on the journey. By acknowledging the challenges, as well as the need for time and dedicated resources to get it right, they are uniquely placed to shape a clear and realistic strategy. With ambition, the drive to transform their organisation and a commitment to making a positive impact on society, they can unlock the value of a more diverse, responsive and resilient supply chain.

References

¹ In this whitepaper, the term ‘procurement’ refers to the full lifecycle from an organisation identifying its needs / requirements, to planning and undertaking sourcing activity, contract and supply chain management and finishing with the to the end-of-life or disposal of assets.

² Social Procurement is a term used by the Victorian government in Australia in its Social Procurement Framework. Broader Outcomes is a concept used by the New Zealand government in its Government Procurement Rules.

³ https://www.dca.org.au/di-planning/supplier-diversity

⁴ Global Public Procurement Database: Share, Compare, Improve!, The World Bank https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/03/23/global-public-procurement-database-share-compare-improve#:~:text=Overall%2C%20public%20procurement%20represents%20on,be%20lost%20due%20to%20corruption

⁵ https://www.bain.com/insights/supplier-diversity-how-to-overcome-four-key-obstacles/

⁶ https://hbr.org/2020/08/why-you-need-a-supplier-diversity-program#:~:text=A%20diverse%20supplier%20is%20a,%2Downed%20enterprises%20(WBEs)a

⁷ https://www.bain.com/insights/shock-proof-how-to-forge-resilient-supply-chains/

⁸ There are many definitions of the ‘social licence to operate’ but the key concepts used here have come from the Sustainable Business Council, New Zealand’s Social Licence to Operate Paper.

⁹ https://www.bain.com/insights/supplier-diversity-how-to-overcome-four-key-obstacles/

INSIGHTS

RESOURCES & DOWNLOADS